A letter from a composer; feedback from a performer

Share

I sometimes get emails from composers asking me to play their piece, or at least take a look at it. I always look, but nearly never play them. I haven’t performed a piece by another composer (other than myself and arrangements I’ve made) in about 15 years. But I am always curious, and am always happy to provide feedback.

Such is the case with a note I received this week from Erin:

It would mean a lot to me if you were to take a look at this piece I've written for bass clarinet (link below). I'm not currently in a position in my career where much of my work gets performed, so it would be really valuable to hear any critical input a performer's perspective.

Composers need performers, and performers need composers. Living ones, on both sides.

Harry Sparnaay reinforced something I always kind of knew: composers and performers need each other. Especially with a relatively young instrument like the bass clarinet. I have commissioned and performed about 150 pieces in my time on this planet, which is nothing compared to Harry, who commissioned over 800 pieces in his lifetime.

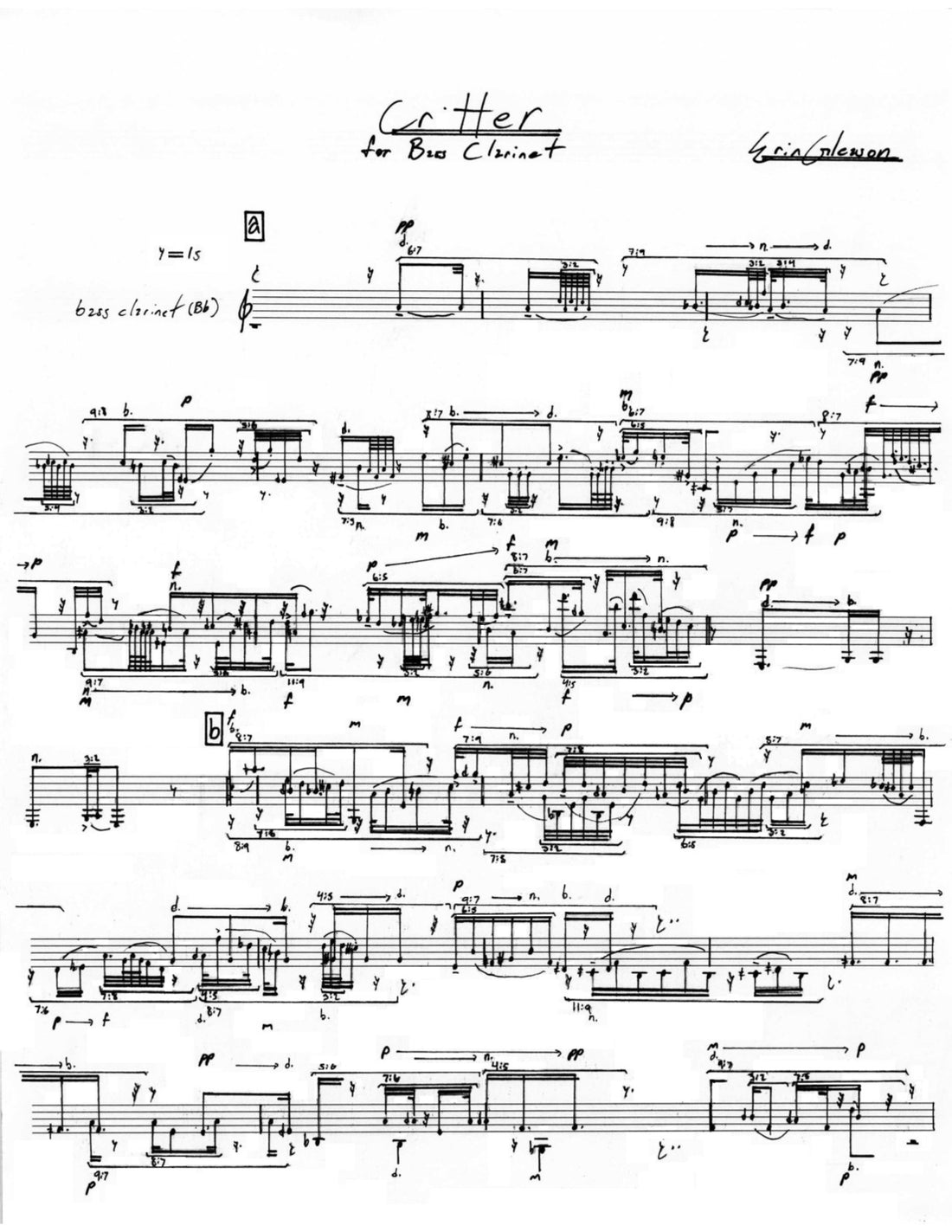

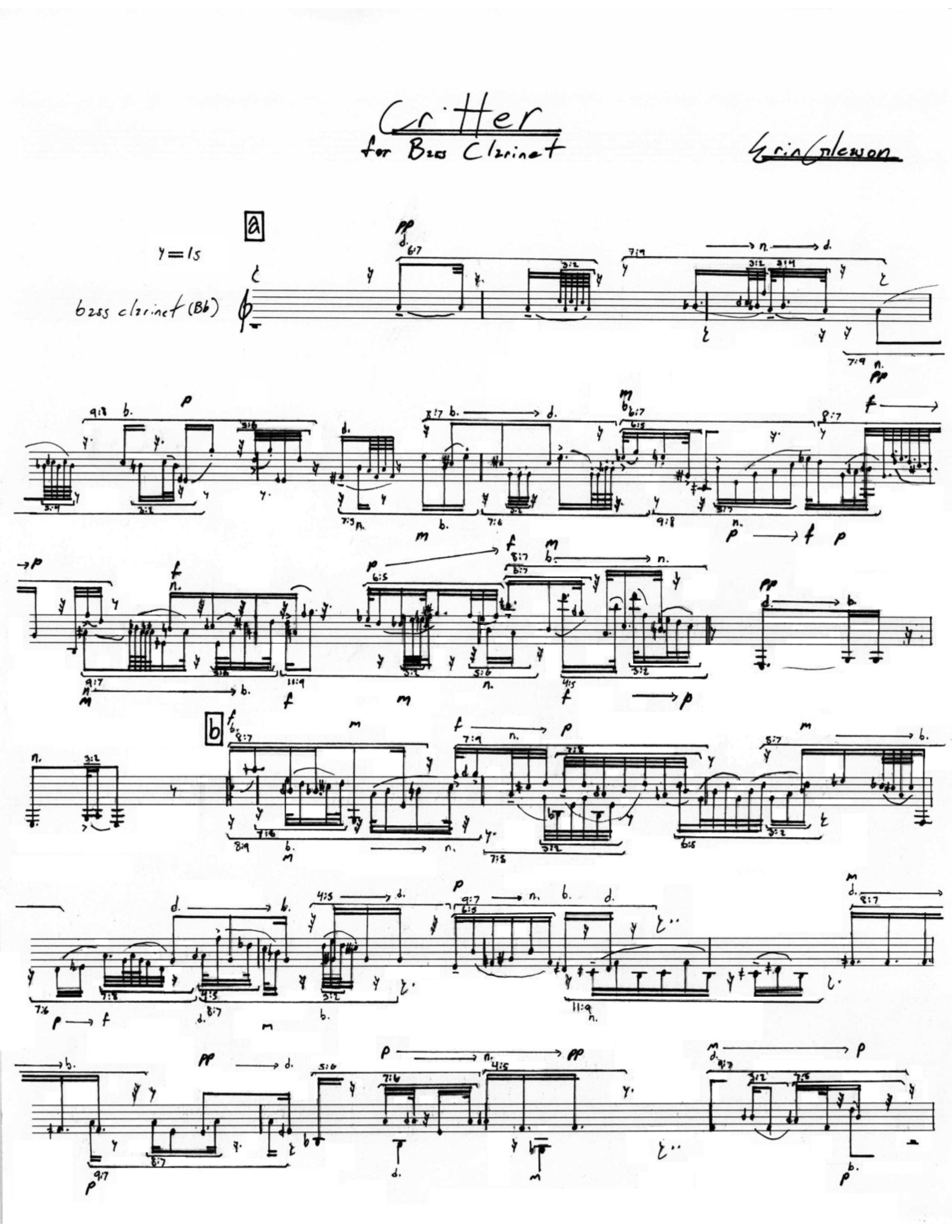

So providing feedback is something I’m happy to do — even if I’m not in a position to program or perform Erin’s piece. Anyway, on the left is the first page of the score, so you can have a look and follow along with my response, which goes like this:

My response:

Thanks for reaching out. I took a look at the score, and it reminds me a lot of the type of work I was learning back in the 80s with Harry Sparnaay in Holland. It’s got a bit of a retro look (hand-written with long, thin stems), which also gives me that impression.

My primary observation: your precise style of rhythmic notation (6:7 and 7:9 in the first line alone) tends to force players into a box; players want to be precise, and execute what the composer clearly intends. Put another way, players assume that if there’s ink on the page, it’s meant to be adhered to. Sometimes composers are trying to notate what is in their head, and if what’s in their head is gestural, it can be difficult to put in writing. As a result, many composers become overly prescriptive in their writing. I’m not saying this is the case here, but it’s something I’ve seen throughout my career working with composers. And, when working with these composers, as often as not, they prefer an approximation of the rhythm if it helps to bring out the gesture. Again, while I’m not sure this is the case with your piece, the title alone indicates that it’s programmatic, and somewhat gestural in nature.

Also, from a notation perspective, you seem to be notating two different “critters” — I glean this from the upward vs. downward stems and beaming. If I’m right about your intent, this might be easier to read if it were actually on TWO different staves. Again, back in the Sparnaay days, many composers wrote in a grand staff (even if both parts were in treble clef) to simplify their intent of a true “conversational” type of polyphony.

Performance-wise, your writing requires the player be able to “turn on a dime” — and that can be a real challenge for most bass clarinetists. Large registral leaps with dynamic changes are hard to execute precisely. Your writing is vaguely reminiscent of Brian Ferneyough’s “Time and Motion Study,” and is typical of composers of the New Complexity movement. (BTW, even Ferneyough, who wrote some of the most complex music I’ve ever seen, with dynamics and articulations and microtones on each note, preferred gesture to precision.) I get what you’re trying to do here, it’s just hard to pull off. Not impossible, but really hard.

Which brings me to my main point as a performer. (Note: I mean this as one man’s viewpoint, and no more.) I look at a piece of music as a value proposition for myself and for an audience. By this I mean, I look at its length, its potential to move an audience, and the amount of effort I estimate it will take for me to learn it to the point I can reach that potential.

I can move an audience with a 5-minute Beatles arrangement, which has a good chance of delighting a broad group of people—with a fairly minimal effort to prepare it. In my calculus, I see this as a “good value” for me, because I can have a piece in my repertoire that is a fairly “sure thing.” But, let’s say that Beatles arrangement flops with an audience; the time “lost" preparing it is not too extreme, and I can abandon the piece in favor of something else.

Now, compare that with a piece like Critter: I would anticipate this 5 minute piece would take several weeks to work up to the level where I could successfully interpret it for an audience. Even if I was able to nail it, there’s no guarantee that it would be effective. I believe a good performer is one that can “sell” each piece to an audience by sheer force of craft and charisma, but it’s not always well-received, as we all know.

So in these cases, if I’m on the fence, I think: would the “juice be worth the squeeze” for me? I ask myself this question as a professional performer with a limited amount of time to spend learning new works. Would this piece last in my repertoire? Would I get a lot of “mileage” out of the piece? Is it universal enough to be performed in a concert hall AND a coffee shop? These days more music is performed outside the concert hall than inside. So as a composer AND a performer, I think about the practicality of the music I write. I can’t afford to be purely idealistic about my art. These are the considerations I make when thinking about a piece—even ones that I write, and I hold other composers to this standard, too.

Finally, I’m aware I may not be normal. I love popular culture and infuse it in the pieces I write. I care about the audience more than I care about the composer (or myself). I care about building community through music that has a shared context. And, most importantly, I’m at the point in my playing career where I am very, very picky about what I play.

I am glad you sent me this. Thank you for asking for my opinion; I hope my reply has been helpful.

So, what do you think?

I know I may a unique opinion about this subject, so I would welcome a discussion if you have anything to add for Erin!

And, thanks for reading!

-Mike

3 commentaires

I’m 71 and started composing at the age of 14 living out an urgent sense of destiny. I have composed in every medium (orchestral, chamber, opera, etc) so I’m not new to anything. Inspired by mostly neoclassical composers like Hindemith, Milhaud, Martinu and I others, my work is carefully crafted, written with musicians in mind and never given to chance operations. From my experience, I see no logical reason to preserver, to keep racking up compositions since no one has ever shown me any interest unless I paid them to perform something. It always sounds nice when people say composers and musicians should work together, but if it’s all about money, then composers ought to learn how to be wealthy so they can finance their own work because the average musician could care less about most composers.

Gardner Read summed it up as follows: "If the composer says in effect to the performer: ‘I do not care whether you perform my music or not,’ we cannot argue the matter. But if he indicates: ‘I want you to perform and respond to this music,’ then his fundamental duty is to write his music so that it is accessible to interpretation. When the performer cannot approach the composer’s meaning because of capriciously obscure notation, he may in effect say to the composer: ‘Why should I bother to puzzle out your music?’ "

I think it’s so important that composers work with performers to gather insights about what “lays well,” or even what performers enjoy or don’t enjoy executing (granted, it is a “focus group of one” but that is better than a “focus group of zero.”)